Countries of all stripes – whether developed or underdeveloped, democratic or authoritarian – have been known to commit strategic military miscalculations. The U.S., for example, won decisive wars against developed countries such as Germany and Japan, but blundered in wars against much lesser powers like Vietnam in the 1970s and Iraq and Afghanistan after the 9/11 attacks.

Strategic military miscalculation usually results in the collapse of authoritarian regimes. The decision of Argentina’s military junta to invade the Falkland Islands in 1982 led to its defeat in the war against Britain and the fall of Gen. Leopoldo Galtieri’s regime. Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990 led to a military disaster for the Iraqi army following Operation Desert Storm, paving the way for the 2003 U.S. invasion of the country and the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime. Successful countries eventually accept the need to revamp their political systems, initiate democratic reforms and champion world peace. It took Germany, whose army fought exceptionally well operationally and tactically, two world wars to metamorphose. It took Japan’s disastrous defeat precipitated by the Pearl Harbor attack to convince Tokyo to change. Under U.S. direction, the two countries transformed into full-fledged democracies.

Since the turn of the 20th century, political leaders, heads of state and political movements in the Arab world have also shown a propensity for massive miscalculation. Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack is a prime example, but it was precipitated by several other cases that have shaped the region since World War I.

Hamas’ Miscalculation

Hamas’ rationale for last month’s attack stemmed from its conviction that Israel, with U.S. backing and Arab acquiescence, intended to eliminate any possibility of Palestinian statehood. By taking Israeli hostages, it also intended to secure the release of thousands of Palestinian prisoners being held in Israeli jails, knowing that Israel has in the past been willing to conduct prisoner swaps. (In 2011, Israel released more than 1,000 Palestinian prisoners to secure the release of Gilad Shalit, an Israeli soldier detained by Hamas for more than five years.) However, Hamas failed to consider the likelihood that Israel’s war Cabinet would launch an unprecedented air and ground campaign following its attack, the scale of which recalled the genocidal horrors ingrained in Israel’s collective consciousness.

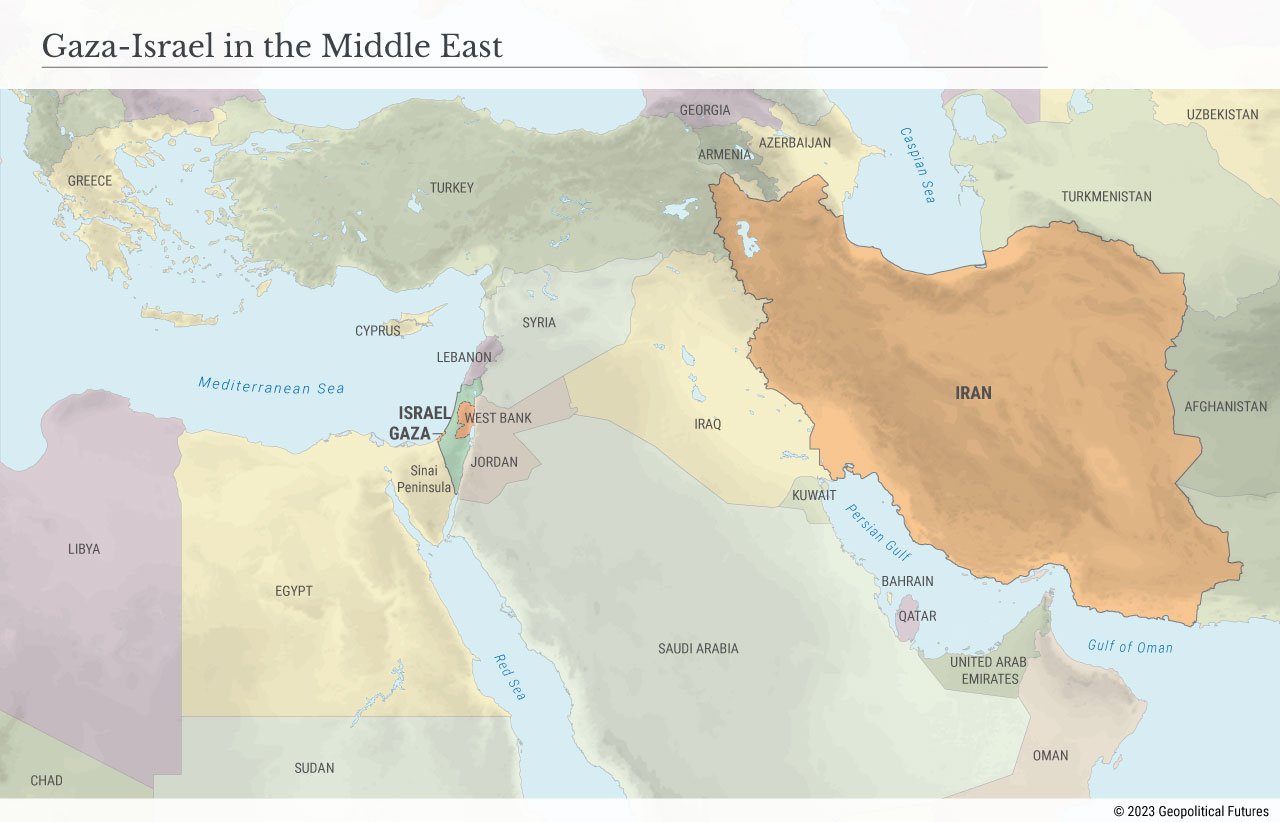

Hamas expected Israel to plead for negotiations to secure the freedom of some 240 Israeli captives. Images from Gaza on Oct. 7 showed Hamas guerrillas ecstatic about the possibility of a massive prisoner swap. But Israel instead unleashed a withering military campaign. Moreover, Hamas did not inform Iran and its regional allies in advance about its plans. It assumed Hezbollah would join the fighting from southern Lebanon and that Iraqi militias in Syria would engage Israel from the Golan Heights. Hezbollah’s unenthusiastic involvement in the war has cost it far more casualties than Israel and did not relieve even the slightest pressure on embattled Hamas. Hamas was left stunned by its allies’ tepid response, having previously believed its attack would transform the Middle East and pave the path toward establishing a Palestinian state. An extraordinary summit of Arab and Islamic countries held last month in Saudi Arabia resulted only in generic statements of support for the Palestinians and demands for the immediate cessation of hostilities. Hamas counted on the outbreak of a third intifada, but Israel’s preemptive raids against West Bank activists ruled out this possibility as well.

Arab Revolt in 1916

Hamas’ deadly miscalculation wasn’t unprecedented. The 20th century is rife with episodes of poor decision-making by Arab leaders, beginning with the anti-Ottoman Arab Revolt in 1916. The British feared that Ottoman Sultan Mehmed V’s declaration of jihad in November 1914 against Great Britain, France and Russia (the so-called Triple Entente) would dissuade Indian Muslims from fighting against the Central powers – which included, in addition to the Ottoman Empire, Germany, Austria-Hungary and Bulgaria. The British high commissioner in Egypt, Henry McMahon, tried to convince the emir of Mecca, Sharif Hussein bin Ali, to declare jihad on the Ottoman Empire in exchange for creating an Arab Kingdom in West Asia. In June 1916, Hussein launched the Arab Revolt, unaware that Britain and France had already signed five months earlier the Sykes-Picot agreement, which gave administration over Iraq and Palestine to London and over Syria and Lebanon to Paris. The British also promised the emir of Najd, Ibn Saud, to include Hejaz in his rapidly expanding emirate.

McMahon clarified to Hussein that the Arab kingdom would not include Palestine. Hussein’s son, Faisal, who was proclaimed king of Syria in 1920, had communicated with the president of the Zionist Organization, Chaim Weizmann, and accepted the Balfour Declaration, which promised to establish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. He later rescinded this agreement due to Arab opposition. Faisal also heeded the recommendation of the U.S.-sponsored King-Crane Commission, which called for autonomy of mainly Christian Mount Lebanon.

Despite Sharif Hussein’s concessions, the interests of Britain and France prevailed against those of the Hashemites. Nevertheless, in partial fulfillment of their promise to them, Winston Churchill, then secretary of state for the colonies, declared Faisal king of Iraq in 1921 and his brother, Abdullah I, emir of Transjordan. However, Britain found working with Ibn Saud in Arabia more practical. The British allowed Ibn Saud to extend his territorial authority to Hejaz, provided he did not impinge on Britain’s sphere of influence in the Persian Gulf emirates, Transjordan and Iraq.

1948 Blunder

The Arab summits over the Palestine issue in 1946 in Egypt and Syria did not refer to military intervention in Palestine. They primarily rejected the recommendations of the Anglo-American Commission, which called for creating two states in Palestine, one Jewish and another Arab. They also promised to provide Palestinians with financial aid. Even the Egyptian secretary-general of the Arab League, Abd al-Rahman Azzam, totally opposed the war and advocated negotiations with the Zionist movement. Prominent politician Sidqi Pasha told Egypt’s Senate that the army was unfit for war and would lose if it took on the Haganah, a Zionist military organization that represented the Jews before Israel’s establishment.

King Farouk made the surprise decision to invade Palestine in 1948 against the recommendation of the Egyptian army and Cabinet – despite Prime Minister Mahmud Nuqrashi Pasha’s belief that the Palestine question was not a matter of vital national interest, and the Cabinet’s vote against committing the military to war. The army’s chief of staff did not believe the troops could go to war, let alone win, in part because the army deemed more than 80 percent of military-age Egyptians unfit for military service due to rampant hepatitis, schistosomiasis, malnutrition and illiteracy.

In the first communique broadcasted by the coup plotters on July 23, 1952, Anwar Sadat claimed that bribable officials in the defunct regime had purchased defective weapons, including artillery that exploded when firing during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, leading to the defeat of the Egyptian army. However, investigations after the fall of the monarchy concluded that three artillery units exploded during loading due to poor training, not malfunctioning.

Egypt lost the war due in part to the lack of coordination with the Iraqi army and Jordan’s Arab Legion, the best-trained and most efficient army during the war, and in part to militarily unfit Egyptian troops, the absence of a war strategy and low morale. Farouk was determined to prevent the Hashemites in Iraq and Jordan from becoming the most significant royal power in the Middle East. At the same time, the Hashemites hoped to blunt Farouk’s ambition, especially since he entertained the idea of resurrecting the Islamic caliphate, which was disbanded in 1924 by Turkey’s Kemal Ataturk, and declaring Cairo its capital city. The Hashemites had achievable objectives, while Farouk had visions of grandeur.

Suez and the Straits of Tiran

Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser made a grave mistake when he nationalized the Suez Canal in 1956. His decision led three months later to the outbreak of the Suez War, which saw Britain, France and Israel declare war on Egypt, resulting in a disastrous military defeat for Cairo.

At the time of the canal’s nationalization, just 12 years remained of the original 99-year Anglo-French concession. Yet, the material losses that resulted from its nationalization, such as the seizure of Egyptian assets in European banks and the compensation paid to foreign shareholders, far exceeded the proceeds of nationalization. At the same time, the war and sanctions precipitated the beginning of the collapse of the Egyptian currency. Thousands of Egyptian soldiers and civilians were killed, and most of the hardware that Nasser had procured from former Czechoslovakia was destroyed. The war also destroyed modern European-style cities built by the British and French along the Suez Canal, such as Port Said, Port Fouad and Ismailia, and displaced hundreds of thousands of Egyptians. Furthermore, the U.N. General Assembly established the United Nations Emergency Force to patrol the border with Israel, stationed in the Sinai Peninsula, the Gaza Strip and Sharm el-Sheikh, allowing Israeli ships to cross the Straits of Tiran to the Red Sea for the first time since King Farouk banned them in 1950. Nasser’s reversion to the status quo ante in 1967 triggered the Six-Day War.

Egypt’s military was defeated, but diplomatically the war was a success. U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower coerced the tripartite alliance to pull out of Egypt, and Nasser’s prestige as the champion of Arab nationalism soared. During the interwar period leading to the 1967 war, Nasser bragged about building the most potent armed forces in the eastern Mediterranean. However, his Arab critics ridiculed him for allowing Israeli shipping through the Straits of Tiran. Over time this issue soured Nasser’s image, and he waited for an opportunity to undo it.

His chance came in May 1967. The Soviet Union warned Nasser about an Israeli military buildup near the Golan Heights in preparation for invading Syria. It was a false alarm, but even after discovering this, Nasser sent his army to Sinai in a spectacular military parade without intending to go to war. He also decided to block Israeli shipping from the Gulf of Aqaba into the Red Sea. Israel considered Nasser’s action as a casus belli and decided to complete the unfinished 1948 war.

The operational problems that plagued the Egyptian military in the 1948 and 1956 wars were still apparent in 1967. The Egyptian armed forces were unprepared for war, given their poor and politicized leadership and insufficient training. Moreover, Nasser assumed that the U.S. would resort to secret diplomacy to defuse the crisis. In 1960, during the union years between Egypt and Syria, Nasser sent his army to Sinai to relieve the pressure on the Syrian army after a major confrontation in the Golan Heights. Eisenhower used his leverage with Israel to restore quiet along the northern armistice line. But in 1967, President Lyndon Johnson’s administration, fed up with Nasser’s anti-American rhetoric, gave Israel the green light to launch the war. Israeli forces swept to victory against Egypt, Syria and Jordan. The political mood in Washington had changed, and Nasser’s failure to understand it caused a geopolitical earthquake that is still reverberating throughout the region.

Iraq’s Invasion of Kuwait

Iraq won the 1980-88 war with Iran but emerged economically battered from it. To cover the cost of the war, Iraq had borrowed billions of dollars from Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. Unlike the Saudis and Emiratis, who wrote off Iraqi debt, Kuwait insisted that Saddam Hussein repay the $14 billion that Iraq owed. Iraq accused Kuwait of exceeding its oil production quota to lower crude oil prices, an untenable situation for Iraq, whose oil revenues were insufficient to cover the salaries of the bureaucracy and the large standing army. Baghdad also accused Kuwait of stealing Iraqi oil from the Rumaila oil field through slant drilling.

Saddam did not comprehend the complexity of international relations. He had spent years in prison and had not completed his college education. The only non-Arab capitals he had visited were Moscow and Paris. He did not grasp that Iraq, a country carved out by Britain in 1921, could not erase Kuwait, another country created by the British. Saddam based his decision to invade Kuwait on a cursory conversation with April Glaspie, then U.S. ambassador to Iraq, who told him that the U.S. had no policy on intra-Arab relations, which he understood to mean that the U.S. would only verbally condemn the invasion of Kuwait. He believed that invading Kuwait before the impending collapse of the Soviet Union would spare him the wrath of the U.S., unaware that the bipolar international system that shielded Third World countries already had ceased to exist.

Saddam’s reckless decision to invade Kuwait decimated the Iraqi army. A multinational military coalition intervened to reinstate Kuwait’s independence, and Iraq was subjected to severe sanctions, marking the end of its status as a rising regional power. In 2003, the U.S. invaded Iraq and toppled Saddam’s regime, enabling Iran to creep in and dominate the country.

Misunderstanding How the World Works

Arab leaders, engrossed in a distorted worldview, tend to see the world through the prism of their domestic politics, often failing to comprehend the complexity of international relations. Arabs in high office are autocrats who do not answer to anybody else, driving them to make fateful decisions. Many Arab leaders live in echo chambers, making decisions premised on faulty assumptions, inattentive to how their antagonists might respond. The consequences have played out time and again, including today in Gaza.

By Hilal Khashan - GeopoliticalFutures